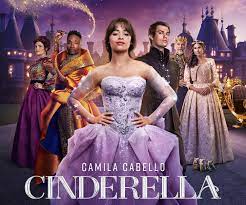

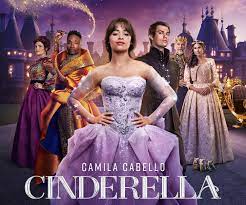

So why did this seemingly progressive Cinderella story backfire? Is it possible that these old fairy tales just can’t be recreated in a modern lens?

The core of the problem lies with reinventing Cinderella herself. Cabello’s Cinderella is more independent than past Cinderellas; her dreams to start a business are new, maybe even innovative. But Cinderella is so free-spirited that she comes off as cold and even rude. With almost all the characters Cinderella meets, she rolls her eyes at them and says some cheeky remark. On the surface, she seems to care about little else besides her business. Her character implies that to be a “strong woman”, you have to narrowly focus on a single path and disregard virtually everything else. In Cinderella, many of the other female characters are either, like the title character, single-minded models of feminism or flighty, hopelessly romantic airheads. These traits are not mutually exclusive, but the movie portrays them as such. If anything, this does a disservice to the characters, casting each of them into one of these two camps without much room for change.

Cinderella herself shows the black-and-white mindset the movie has regarding femininity. At first, she mocks the ball and the very idea of love. But when she meets the Prince, the original story is left mostly intact: they immediately fall in love and dance, singing Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect” as they do. Almost immediately after, Cinderella denies the Prince’s advances because she thinks marrying will end her dreams of a fashion designer job. It’s as if the movie is stuck in this idea that marriage and career must be separate from each other and, as such, romantic scenes have to be separate from “feminist” scenes. In reality, a woman’s romantic aspirations or desire to marry doesn’t diminish her strength. The idea of feminism is that anyone, regardless of gender, should be able to pursue the dreams they have, whatever those are and however many they have, without barriers. When Cinderella’s central conflict pits love and ambition against each other, it insinuates the idea that a woman can’t have both, that to follow one instinct is strong, and to follow the other is weak.

And though the familiar story of Cinderella may have some outdated details, there are better ways to modernize and empower it. 2015’s Cinderella doesn’t make any revolutionary changes to the story, but Cinderella’s conviction is firmly rooted. Throughout the movie, she chooses kindness first, following her values before anyone else’s. She may willingly marry the Prince, but she’s a strong, fully realized character who doesn’t compromise her values. So she may not directly preach anything about feminism, but she is still a powerful role model. 2021’s Cinderella is a worthwhile attempt to address the story’s old-fashioned traditions, but its additions are confusing and unmemorable in their execution—and, just like the Fairy Godmother’s transformation, won’t last for long enough.